by Martin Fletcher

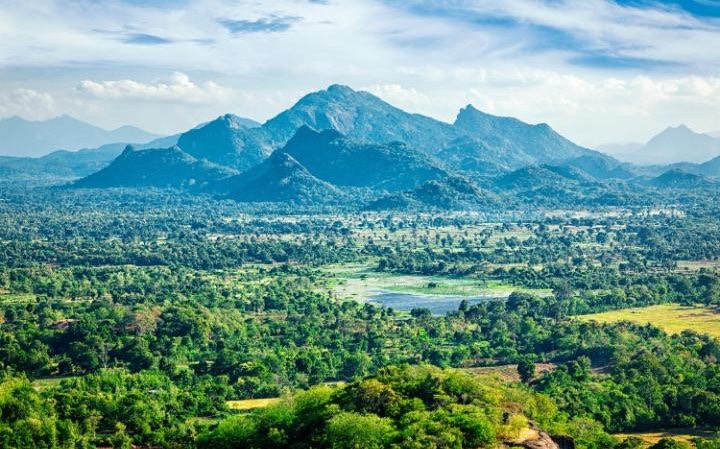

I celebrated Easter morning with my wife this year on an island of sun-warmed rock in a huge lake fringed by forests and mountains in eastern Sri Lanka’s remote, little-known Gal Oya National Park. We were alone except for our guide and a few faraway fishermen in dugouts with makeshift sails. We bathed in the clear, warm water. We ate a breakfast of fresh fruits, curd and honey laid out on rush mats sprinkled with flowers. A white-bellied sea eagle circled in the cloudless sky. Lizards scurried away. From neighbouring islands came the cries of peacocks. This was the same serene, sublime Sri Lanka that Katy and I remembered from our honeymoon in 1982.

Back then we had meandered along deserted roads on a motorbike, narrowly escaping disaster when a chicken flew into my arms. We stayed in beach huts in somnolent fishing villages. We lived in the sun and it seemed like paradise, especially during the English winter from which we had escaped.

The arrival of war

But 1982 was the year before more than a quarter of a century of civil war erupted between Tamil separatists and the government, leaving an estimated 100,000 Sri Lankans dead. It was before the tsunami that killed at least another 30,000 in 2004 , and before the advent of the distinctly mixed blessing that is mass tourism.

We had been apprehensive about returning. We doubted whether the Sri Lanka that so enchanted us 34 years ago still existed, but we were wrong. It emphatically does. Moreover, the war zones of the north and east, including Gal Oya, are no longer off limits, and a string of stunning boutique hotels have recently opened in choice locations, with gastronomy to match. No more cheap dives for us. We’re too old.

Testaments to the past

The north, erstwhile stronghold of the Tamil Tigers who pioneered suicide bombs, carried out political assassinations and terrorised even their own people , was new territory for us. We went by train from Colombo to Jaffna on a line that reopened only in 2014, past shattered homes and a water tower toppled by the Tigers and left as a monument to the “futility of terror”.

At Elephant Pass, gateway to the Jaffna peninsula, a huge memorial celebrates the government’s “steadfast political leadership, unshaken as a mountain, which brought to an end the era of terror” – but fails to mention its massacre of innocent Tamil civilians. Nearby stands a bizarre armour-plated bulldozer which the Tigers filled with explosives and directed towards a military base until a heroic young soldier blew it – and himself – up with grenades.

In Jaffna itself, behind a billboard proclaiming “Say No to Destruction. Never Again”, stand the ruins of a library that housed a priceless collection of Tamil literature until it was torched by a Sinhalese mob.

A return to peace

Happily, the colonial heart and fine Hindu temples of Sri Lanka’s most Indian city survived largely unscathed. Jaffna is rebuilding and determined to move on. It has much to offer, not least the string of remote, palm-fringed islands that form the fractured tail of the upended comma that is Sri Lanka.

A series of low bridges and a rickety old ferry took us to one of the most distant, Nainativu , site of a well-known Hindu temple where newborns are brought for blessings, but what bewitched us was the scenery – the almost imperceptible merging of shallow lagoons and pancake-flat land beneath a vast blue sky.

Elsewhere, the Sri Lanka of our honeymoon not only survives but thrives. It remains a singularly beautiful land of lush jungle and paddy fields, of misty hill country carpeted with the vivid green baize of manicured tea gardens, of white beaches and impossibly blue sea. It still blazes with jacaranda, frangipani and bougainvillea . Its trees are heavy with mangos, papayas, avocados, jackfruit, coconuts and bananas. A walking stick planted in its fecund earth would sprout.

The bird-life is astonishing – hornbills, painted partridges, crested serpent eagles, racket-tailed drongos, kingfishers, bee-eaters and brahminy kites, to name a few. So are the animals – crocodiles, leopards, wild boar, monkeys, mongooses, snakes and elephants. Because the British shot almost all Sri Lanka’s tusked elephants, the descendants of those that survived are mostly tusk-less, so immune from poachers.

Age-old marvels rediscovered

Journeys remain visual feasts – whitewashed Buddhist stupas and ornate Hindu temples, exotic fish and fruit markets, women doing their washing in lakes or streams, gaggles of tiny schoolchildren in white uniforms, impromptu cricket games on strips of dust, buffalo with tick-seeking egrets balanced on their backs. Sri Lanka has largely escaped Western homogenisation, so far. Squalid, Indian-style poverty is rare. The people are so welcoming that our driver insisted on addressing me – rather disconcertingly – as “my darling boss”.

For older British visitors, at least, there is still the poignant appeal of our fading colonial legacy: stone churches with crumbling gravestones, tea gardens named Henfold or Glenmore, red George VI-era pillar boxes , Morris Minors and those ultimate symbols of British punctiliousness – the clock towers in the centre of most big towns.

One consequence of the war’s end is an explosion in the number of tourists – from 400,000 in 1982 to more than 1.5 million last year – and some unfortunate coastal developments. But it is not hard to avoid the scrum. Coachloads visit the ancient city of Anuradhapura , but steer clear of the main sites and you can wander alone among ruins of 2,000-year-old monasteries and temples shaded by venerable banyan trees.

In Yala, the country’s most popular national park , a guide spotted a leopard sleeping on a rock and several dozen Jeeps swiftly converged on the spot, creating a noisy, exhaust-belching traffic jam worthy of London. But an hour earlier we had watched, alone and in awe, as six elephants, including a baby, emerged from thick bush right behind us.

In the old hill capital of Kandy we found long queues outside the famous Temple of the Tooth, alleged repository of one of Buddha’s teeth . But right by it we discovered an unexpected gem – the Garrison Cemetery, an acre of shaded tranquillity founded by the British in 1822. The elderly, barefoot caretaker, Charles Carmichael, a Sri Lankan with a Scottish ancestor, proudly showed us the graves of the last Briton killed by a wild elephant; of William Mackwood , impaled on a stake while alighting from his horse; of Captain James MacGlashan who survived Waterloo but not a malarial mosquito; and of numerous victims of cholera, dysentery or jungle fever, including five boys from one family and three sisters, the oldest 19 months, from another.

Ships that had delivered tea and coffee to Britain brought the gravestones back, Carmichael told us. Thousands visit the temple each day, barely half a dozen this bitter-sweet monument to British colonialism.

Galle Fort, on the south coast, is enclosed by 17th-century Dutch ramparts, which saved it from the tsunami in 2004 , and it has become a tourist mecca. But amid the proliferating gift and gem shops stands a musty English lending library, unchanged in a hundred years, where old men go to read the newspapers. Nearby, hidden behind a police compound, we found the “Black Fort” – an abandoned prison from the 1700s replete with mouldering cells and rusting iron gates.

One gorgeous morning in 1982 Katy and I hiked alone across Horton Plains, a Scottish-style moorland high in the hill country full of trout streams, gorse and rhododendrons, to a terrifying sheer drop of 2,800ft called World’s End. We longed to return, but found Horton Plains is now a national park with an exorbitant entry fee and a car park jammed with coaches. At World’s End Chinese tourists took selfies while teetering on the edge.

It still provided a magical moment, however: within minutes of our arrival the banks of dense white mist that were obliterating the view miraculously lifted to reveal a panorama of miniature forests and tea gardens far below.

Sri Lanka’s next-generation hotels

The exclusive new hotels – the sort our youthful selves could never have dreamed of or afforded – also provided moments to cherish. From Gal Oya Lodge, after our Easter-morning breakfast, we drove deep into a jungle once infested by Tamil Tigers, swung on vines as thick as forearms, and swam in pools beneath some rushing waterfalls on which few foreigners would ever have set eyes.

At the Madulkelle Tea & Eco Lodge near Kandy we “glamped” in a luxurious tent looking across the plunging Hulu Ganga valley to the five bumps of the Knuckles mountains, and woke as the sun rose over that mighty range in an orange blaze that illuminated our tent like a headlight. One magical evening at Ulagalla Resort near Anuradhapura we enjoyed a private barbecue of fresh tuna, king prawns and squid beside a lily pond full of croaking frogs as a full moon rose.

Another balmy night at Chena Huts near Yala we fine-dined on a terrace looking across sand dunes and the Indian Ocean to two distant lighthouses rhythmically flashing in the darkness. At Thotalagala, in the hill country, we enjoyed a champagne breakfast on a lawn with a spectacular 50-mile view over receding foothills to the plains beyond.

Our final day, we cycled down to the coast from Tri, a new hotel south of Galle and a few miles inland, through the sort of timeless bucolic scenes we remembered so well. We followed paths across marshes and rivers, past men harvesting rice in paddy fields, through tiny villages where everyone greeted us.

We stopped to inspect pepper vines, cinnamon trees and exotic cannibal flowers. We stumbled on two huge water monitors – prehistoric-looking lizards each four foot long – basking in the sunshine. We watched a peacock deploying its magnificent fan to court a peahen. We exulted in a sudden torrential downpour that cooled us down and produced a rainbow as colourful as the peacock’s tail. At the beach, we plunged into the never-changing, ever-lovely Indian Ocean.

1982? 2016? Apart from our ages, there was really little difference.

This feature originally appeared in the autumn 2016 issue of Ultratravel, The Telegraph’s luxury-travel magazine.

http://www.telegraph.co.uk