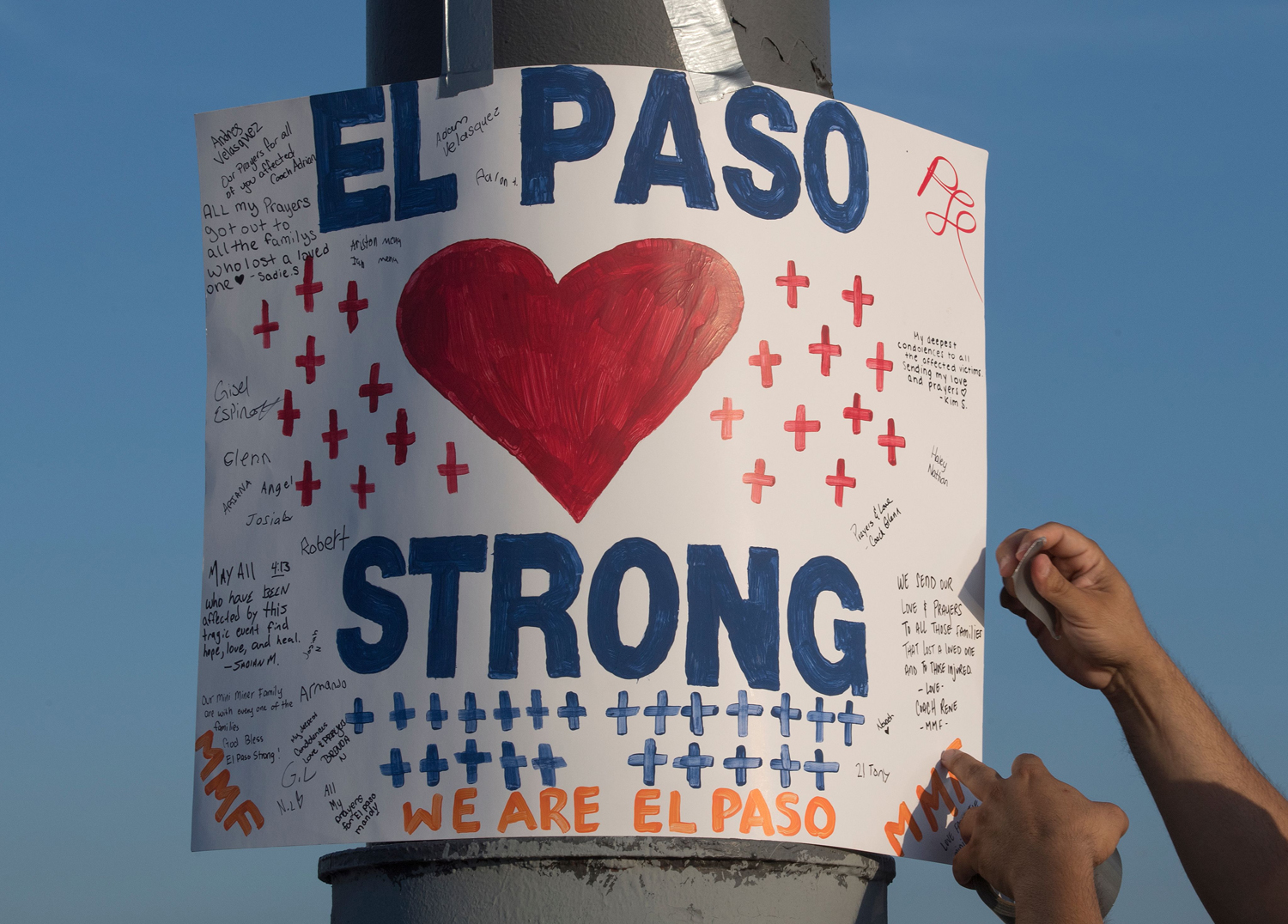

When a series of bomb blasts ripped through Sri Lanka earlier this year, on April 21, my heart went out to the island and its people. Sri Lanka had bravely emerged through a long civil war and its recent ticket as Asia’s go-to fleek travel destination gave its delicate economy a required rousing. But right after the terrorist attacks, many countries issued advisories against travel to Sri Lanka (most of which have since been lifted).

But travel advisories against countries are a questionable matter, one that betrays power imbalances between nations, and leaves lasting perception damage on the country. I have just returned from Sri Lanka – described memorably by Michael Ondaatje as a ‘pendant off the ear of India’ – where i saw the impact of such advisories on its economy. Walking through the charming streets of Galle or Colombo, i saw few tourists at design stores. Restaurants on popular Pedlar Street were bare on a weekend evening. Hotels were running empty. Taxis had no takers. The beach was deserted.

Malik Fernando, a reputed hotelier and founder of the Sri Lanka Tourism Alliance, was concerned by the perception impairment of travel advisories. “Tourism makes up almost 10% of our GDP,” he told me, “and one in ten people depend on it.” At our breakfast in the Welligama Bay, we discussed the politics of issuing caution against travelling out to conflicted turf. But this raises questions of who is in power to mandate such advisories, and whether all countries are vulnerable to these notifications.